Chapter One

Chapter One

“I don’t get it, Mom. If this is our house, why are other people going to live here?” My daughter Melissa, nine years old and already a prosecuting attorney, looked up from the baseboard near the window seat in the living room, which she was painting with a two-inch brush and a gallon can of generic semi-gloss white paint. Never use the expensive stuff when you’re letting a fourth grader help with the painting.

“I’ve explained this to you before, Liss,” I told her without looking down from the wall. I was trying to locate a wooden stud, and the stud finder I was using was being, as is often the case with plaster walls, inconclusive. Using a battery-operated gizmo to find a stud and failing: I tried not to dwell on its metaphorical implications for my love life.

“Other people aren’t coming here to live,” I continued. “They’ll be coming here when they’re on vacation. We’re going to have a guest house, like a hotel. They’ll pay us to stay here near the beach. But we’ve got to fix the place up first.”

“Mr. Barnes says these houses have history in them, and it’s wrong to make them modern.” Mr. Barnes was Melissa’s history teacher, and at the moment, he wasn’t helping.

“Mr. Barnes probably didn’t mean this house. Besides, we’re fixing it up the way it is meant to be. I mean, no one would want to live in the house the way it looks now, right?”

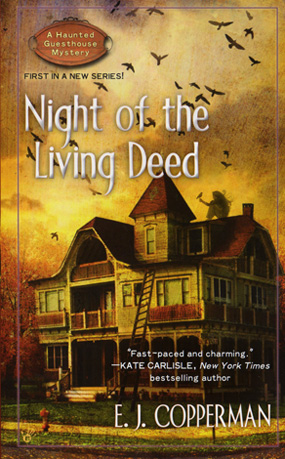

Our hulk of a turn of the last century Victorian house was not, by the standards of anyone whose age was in the double digits, livable. Sure, the house had once been adorable, maybe even grand, but that was a long time ago. Now, the ancient plaster walls downstairs were peeling, and in some places, crumbling. There was a thick coat of white dust pretty much everywhere, and as far as I could tell, the heating system was devoid of, well, heat. The October chill was already starting to feel permanent in my bones.

However, it was clear some work had been done by the previous owner, though by my decorating standards, he or she must have been demented. The living room walls had been painted bright, blood red, and the kitchen cabinets were hideous, and hung so high Shaquille O’Neal would have a hard time reaching the cereal. Luckily, the upstairs walls had been patched and painted, the landscaping in the front of the house was quite lovely (although the vast backyard had been untouched), and the staircases (there were two) going upstairs had been refinished beautifully. It was a work in progress. Slow progress.

“I would live here,” Melissa said, and went back to painting. That settled it, in her view.

“You do live here,” I answered, not noting that there was no furniture, and we were both sleeping on mattresses laid directly onto the floors of our respective so-called bedrooms and living out of suitcases. Why remind her of all the things we’d left in the house in Red Bank after the divorce? Melissa’s father Steven (hereafter known as The Swine) hadn’t wanted the furniture, but he did want half the proceeds when I sold it all to help make the down payment on the house. The Swine.

Besides, now the house was a construction site, and any furniture would be prone to disfigurement or worse while the work went on. As soon as the house was in shape, the new furniture I’d ordered (and in some cases, collected from consignment stores) would be delivered.

I hadn’t put down a drop cloth where Melissa was working, because I was going to paint the rest of the wall after I’d made my repairs, and the wall-to-wall carpet in the living room was among the first things I’d decided to remove when I first saw the house. Giving Melissa woodwork to paint was going to be little help in the long term, but mostly, it was a good way to keep her busy.

I went back to concentrating on the wall. If it were a modern wall, I could knock a hole in the drywall and look inside, then patch it back up, and by the time I was finished painting, nobody would ever know anything had happened. But not in this house. These walls were the original plaster, which afforded them a smooth, gorgeous effect I was planning on exploiting (among many other features) for a higher per-night price. But plaster is not easy to repair, much more an art than a science, and the only people who really knew how to do it had died out at about the same time as drywall became popular. If I breached the wall by more than a small crack, I’d end up having to replace the whole wall, and that would be bad.

I’d decided to open a guest house after my last job, as a bookkeeper at a lumberyard, hadn’t worked out. Mostly, it hadn’t worked out because my boss had a habit of forgetting his marriage vows when he walked over to my desk to discuss the company’s finances. Luckily, there had been multiple witnesses when he tried to put his hands in the back pockets of my jeans, so he didn’t press charges after I decked him. But I decided to sue, strictly on principle. And because the guy was a jerk.

We settled the case for an amount that had seemed like a lot of money, but once I’d done the math on paper, I realized it would only last Melissa and me about two years, and even then, only if we were very frugal in our lifestyle. The alimony from The Swine was not much, and living in New Jersey, a state with some of the highest real estate values—and property taxes—in the country, wasn’t going to be easy on “not much.”

So I’d decided the thing to do was to take the money and put it into something that could start me off in a business capable of sustaining us for years. And that’s when I thought of a guest house.

I’d always wanted to own and run a guest house in Harbor Haven, the town in which I grew up and where we now lived. I liked the idea of people coming in and out, of helping them enjoy the area I loved so much, and of restoring and maintaining one of the majestic homes near the beach that all too often faced a wrecking ball these days. Developers were everywhere on the Jersey shore, even in rough economic times. History was being wiped out in favor of expensive vacation condos, and I hoped I could save at least one such beauty from extinction. Now, knee deep in it and feeling like I had taken on too much, I was still loving it.

The New Jersey shore (“down the shore,” to us locals), contrary to the popular notion of the state, is absolutely gorgeous, and a wildly attractive vacation destination. Harbor Haven had not yet been discovered by teenagers and families with young children, which meant there were no thrill rides, no hideous souvenir shops and no boardwalk here. (All things I had sorely missed as a teenager, but which whose absenses I now considered serious advantages.) The only thing I really missed was the salt water taffy, but you could get that in nearby Point Pleasant.

In other words, the only tourists who came to Harbor Haven were quiet and wealthy. The perfect place to open a guest house … assuming I could get the shambles around me to look like a palace in the next few weeks. My real estate agent Terry Wright had told me people often book summer vacations right after the season ends, especially in November and December. If I wanted to get color brochures and Internet advertising going before people started making their summer vacation plans (and I did), I’d really need to get cracking.

So I steeled myself and let my father’s voice ring in my head. “Alison,” he’d say, “you know perfectly well that no contractor is going to care as much about doing it right as you will. So stop feeling sorry for yourself and just get it done.” Dad had taught me everything he knew about home improvement, which was a lot. Not exactly a general contractor, but more of a “handyman,” he’d spent decades learning about what makes houses—especially old ones—work, and he’d taught me what he knew, “so you’ll never have to rely on some man to do it.” He was never so proud as when I worked at Home Depot and showed some guy how to install a lock, or regrout a bathtub.

It hurt a little to think of Dad; it had been four years since he’d died, but you don’t stop missing someone you love—you just stop obsessing about it. When their memory comes flooding back, it still has the power to wound.

“Is this good, Mom?” Melissa woke me up from my flash of depression to show me the completed baseboard. As I’d expected, there was a good slick coat of paint on about the first four inches of carpet away from the wall, and another one about four inches up above the molding (impressive, considering that indicated multiple brush widths), but the baseboard itself was indeed freshly painted, and Melissa done a nice, careful job for a nine-year-old.

“Very good, Liss,” I answered. I took a few steps over to examine the work more closely. “You have the touch.”

She beamed. Melissa is always looking for approval, and usually deserves it. “Would you do me a favor and go get the ball peen hammer from the kitchen?” I asked her. I didn’t really need the hammer, but if I reached over and carefully removed the two brush hairs from the baseboard while Melissa was in the room, she’d have seen it as a failure and been upset.

“Sure.” She got up and ran into the kitchen. Nine-year-olds never walk; they either run like they’re being chased or shuffle like they’re being dragged. There is no modulated speed.

As I reached over to pull off the first brush hair, which luckily had fallen partially on the wall (so it would leave no finger marks), I heard something heavy fall to the floor behind me. But Melissa was in the kitchen, in the other direction entirely.

I turned, but there was nothing disturbed. Well, old houses creak. Hopefully, this particular noise was not caused by something that would require skills beyond what I knew how to fix.

The first brush hair was easy, but the second one, now that I was under time pressure, would be more difficult. But I had a tweezers in my shirt pocket (always be prepared), and lifted it gently even as Melissa called from the kitchen.

“I can’t reach the hammer!”

Now, it didn’t matter a bit whether I got the hammer, but that was odd, so I stood up straight and walked toward the kitchen.

“What do you mean, you can’t. . .”

I stopped short in the doorway. Melissa was standing in the center of the (mostly) empty kitchen, cabinet doors removed and countertops missing from their spots. That was normal in our current state of repair, so it didn’t bother me in the least.

But what did worry me was that every drawer in my roll-up toolbox was open, and every tool appeared to have been flung around the room. One backsaw was hanging precariously from a nail near the ceiling. Hammers, screwdrivers, wrenches and sockets pretty much covered every surface. If it’s possible for a construction site to look especially messy, that’s what I was staring at now. That bothered me.

“It’s too high up,” Melissa said, pointing at it, sitting on top of the window molding.

“Melissa, what did you do?” I launched myself into the room and started picking up tools.

“Nothing! I thought you did it.”

Oh, please. “Why would I throw my tools around like this?”

“Why would I?,” she asked.

“Come on, Liss. You know I didn’t leave the tools like this, and there’s nobody else in the house.” Although I had to admit, that hammer hanging from the window was awfully high for her to manage. Did she just fling it, and get lucky?

“Well, I don’t know! This was how it looked when I walked in.” She stuck out her bottom lip in a gesture of defiance.

I forced her to look me in the eye. “Really?” I asked.

Melissa’s gaze never wavered, which was unusual. “Really,” she said.

Swell. Now I was beginning to believe her. “Well then, how. . .”

I never managed to finish the question, since I was interrupted by a loud groan of wood and what sounded like hailstones hitting the floor in the hallway just off the living room. That was followed by a loud crash. I was out the kitchen door before Melissa could even turn her head, but she still ran faster than me. We arrived in the living room at the same moment, and stopped dead in our tracks.

The very wall I’d been agonizing over now had a gaping hole, at least three feet tall, right down its center. My visions of retaining the period detail and integrity of the room had been, literally, destroyed. I wanted to cry.

“Why did you do that?” Melissa asked.